Bulletin – December 2019 Australian Economy Being Unreserved: About the Reserve Bank Archives

- Download 630KB

Abstract

The Reserve Bank of Australia has a unique and rich archives. In addition to records about the nation’s central bank, the archives contain records about Australia’s economic, financial and social history over almost two centuries. The extent of the collection reflects the Bank’s lineage, with its predecessor (the original Commonwealth Bank of Australia) having absorbed banks with a colonial history. Consequently, the Bank’s archival collection spans convict banking records through to information about contemporary episodes in Australia’s history. This article explains why the archives exist, how they are managed and plans to make them more accessible to the public.

Introduction

The Reserve Bank of Australia is the custodian of an extensive archives about Australia's central bank, the financial sector and the environment in which they operate. To the surprise of most users of the archives, the records span nearly 200 years of Australia's history. Many of these records predate the Reserve Bank of Australia as it is known today. This article explains why the Bank is custodian of such a diverse and historic collection. It describes the nature and significance of the collection, drawing out features of some of the key series. It discusses how the collection is managed with respect to conservation, public access and the current program of digitisation. The article concludes with a description of plans to support greater access to this asset by both the general public and researchers.

Origins of the Collection

The origins of the Bank's collection are linked to the origins of the Bank itself and the foresight of the first Governor, Dr HC Coombs.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has operated as the nation's central bank since 1960. This follows the ‘separation’ from its predecessor, the original Commonwealth Bank of Australia that was established in 1911. From the time of the First World War, the Commonwealth Bank was required to develop central bank responsibilities (raising money for the war effort and subsequent peace, and full responsibility for the issue of Australia's banknotes from 1924), but by the late 1950s, acting as both a central bank and a trading and savings bank had become problematic.[1] The Reserve Bank Act 1959 separated the commercial activities of the Commonwealth Bank from its central banking functions. The Commonwealth Bank would be renamed the Reserve Bank of Australia and would act as the nation's central bank (and hereafter ‘the Bank’ refers to both organisations to capture the continuity of central banking in Australia). The newly created Commonwealth Banking Corporation would operate as a trading bank. (For more details see Explainer: Origins of the Reserve Bank of Australia.)

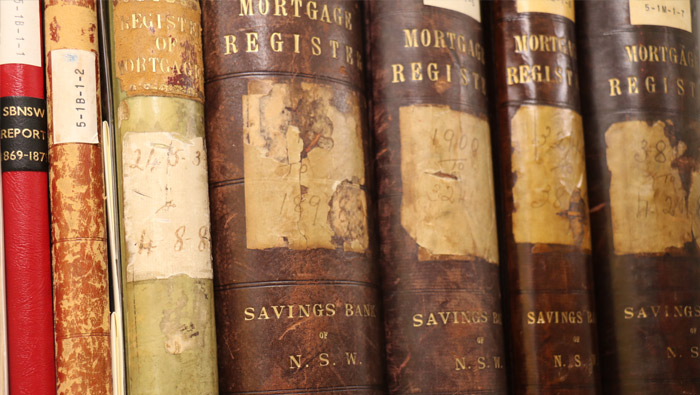

The separation resulted in the Bank inheriting not only the central banking functions of the original Commonwealth Bank but also its archives. So why do the archives span nearly 200 years of history? This is because the Commonwealth Bank had, at key stages, been required to absorb the assets and records of earlier banks. This commenced with the NSW Savings Bank (established in 1819), which was generally known as Campbell's Bank (after colonial merchant Robert Campbell). In 1833, the business and records of Campbell's Bank were absorbed by the Savings Bank of New South Wales (established in 1832 by Governor Bourke). This bank later merged with the Government Savings Bank (established in 1871), which was in turn dissolved in 1931, with its assets and records transferred to the Commonwealth Bank by 1932 – also a government bank.

It is this lineage of government banks in Australia that gives the Bank the unusual privilege of being a custodian of colonial banking records. It also means that the Bank's archives span every major episode of the nation's economic and financial history over the past 200 years. And because economic and financial events, along with the operation of an organisation, happen within a social context, the records also capture key periods in the nation's social history.

The records inherited by the Reserve Bank are of such value, and in good condition, largely because of the foresight and actions of Dr Coombs. Before separation, and while the Governor of the Commonwealth Bank, Dr Coombs recognised the importance of identifying, organising and preserving information so that it can inform public policy and accountability. His role in guiding Australia's post-war reconstruction, and his policy advice on achieving full employment, meant he valued accurate and comprehensive information being readily available to inform decisions.[2] Coombs was also aware of the major Public Service Review of the late 1940s that had identified the problem of poor information management by government agencies, including the destruction of many important records.[3] With debate about the need for a separate central bank already under way, Coombs appointed an archivist to identify and manage records that would be of importance to a central bank and to the nation more generally. (See Box A: Dr Coombs and the Bank's First Archivist.)

Box A: Dr Coombs and the Bank's First Archivist

In 1954, Dr Coombs appointed Jack Kirkwood as the Bank's first official Archivist.[4] Kirkwood was chosen by Coombs because of his strong corporate knowledge (he had worked in the Commonwealth Bank for many years), organisational skills, background in economics and passion for history.

One of Kirkwood's first tasks was to identify records of ongoing value, not only to the Bank but to the nation. He recommended a program of microfilming (the digitisation of its day), so that copies of the most significant or fragile records could be made available to other institutions, both to widen their access and ensure preservation copies existed outside the Bank.[5]

Recommendations for the Bank's records were compiled by an internal Bank committee. These included:

- A central repository to house all the Bank's records.[6]

- Records should remain with the Bank and near to experts (economists) who could assist in interpreting them for researchers and others.

- All records in the repository to be listed and a length of time be imposed upon them to indicate when they could be destroyed or alternatively when they became permanent.

- Access to permanent records to be approved for researchers.

Kirkwood also recognised the importance of promoting the archives. Within a few short years, the Repository had become a popular venue for showcasing records, and tours of the space were regularly given to staff, visitors and other central bankers. A quote in the Bank's staff magazine in 1958 noted that:

‘On the side of public relations, too, the Archives Repository is serving to good purpose. It is now an accepted and very interesting part of the itineraries for visitors inspecting the Head Office building. Indeed the Repository is an achievement of which the Bank is proud and others envious. Officers in or visiting Sydney could profit by a visit and are assured of a welcome by the Archivist.’ – Currency, June 1958

The principles established by Kirkwood and others continue to guide the practices of the Bank's archives today. They were also prescient in foreshadowing principles that would be established for Commonwealth government agencies by the National Archives of Australia.

Nature and Significance of the Collection

The Bank's archival collection comprises a diverse set of banking records that date from the colonial era through to more contemporary activities of the nation's central bank. Their value lies in the primary source material they contain about Australia's economic, financial and social history over the best part of two centuries as well as the volume and continuity of information. This equips the Bank with a good corporate memory, a rich historical context for its operations and decisions, and it supports research and enquiry by citizens on a broad range of topics.

The Bank's colonial banking records date from the 1820s. In addition to information about businesses and other entities, they contain entries about persons. Consequently, these records are rich in social information about individual convicts, ordinary citizens and business people. They afford insights into the development of the Australian economy and financial sector in the 19th century. They also provide details about the formation of the built environment, through records of the acquisition and sale of property and the expansion of branch networks.

The colonial collection commences in the mid-1820s with a small set of records from Campbell's Bank, but largely comprises the records of the Savings Bank of New South Wales (which operated from 1832 to 1914) and the Government Savings Bank (which operated from 1871 to 1932). The time span of the collection captures gold rushes, the 1890s Depression through to the Federation drought. The collection goes beyond the colonial era to include records from the First World War and, in the case of records of the Government Savings Bank, the Great Depression of the 1930s. While some other cultural institutions also have colonial banking records, those held by the Bank are unusual in their scale and completeness, with a lengthy and continuous time series of information across many categories of banking business.

The records relating to the Bank are also unusual in their scale and continuity. They span the establishment of the Commonwealth Bank in 1911 through to the formation of the Reserve Bank and the recent past. Consequently, they capture over 100 years of the evolution of central banking in Australia and document the development of each of the unique functions of a central bank: government banking; payments system oversight; market operations; monetary policy; financial stability; and banknote issuance. The way in which these functions are fulfilled is informed by the economic, financial, political and social context of the day, with archival records providing this information. The central bank records encompass major events of the 20th century, including the two world wars, international and domestic financial crises, historic swings in economic conditions, regime changes in the operation of markets (for goods, labour and assets) along with changes in the framework for monetary policy. And with deliberations by central bankers informed by the economic and financial evidence, the archives provide a comprehensive collection of data, including those that predate the provision of official statistics. How the central bank has conducted itself as an enterprise is also captured in the collection, with records providing insight into matters ranging from governance, the use of technology through to the workplace norms of different eras.

As can be expected of archives that span so many years, the records come in a variety of media and formats. While most are paper records, media range from the vellum of the oldest mortgage document, to glass plate negatives, photographs, film and audio-visual material, digital files and even metal banknote printing plates. A given medium can also come in many formats. Considering paper records alone, they take the form of ledgers, folios, pamphlets, plans, posters, vouchers and stamps through to actual banknotes (issued and unissued). Media and format are themselves additional information (or metadata) that enriches a record. The diversity of the media and format of the Bank's archival records adds to the range of enquiries that can be undertaken with them, further enhancing their significance.

Management of the Collection

The Bank's archives have two components: all records of continuing value to the Bank and those records that have been identified by the National Archives of Australia as of continuing value to the nation. In this case, the National Archives specifies the records that should be kept permanently and these are retained by the Bank in trust for the Australian people.[7]

In terms of scale, the Bank's archives comprise nearly 4,000 shelf metres. Owing to this scale, the conservation and security needs of the collection, and the suitability of the Bank's facilities, the Bank is one of only a few organisations that have been given dispensation by the National Archives to hold archival records on their own premises.

The archives are housed in a dedicated custom-designed repository (in a basement of the Head Office building), that complies with the standards for environmental and physical controls required by the National Archives. It has spaces and rooms with differing environmental and security controls to ensure that records are retained in appropriate conditions for their format. The Bank's archivists manage the records, so that they are preserved, controlled and access is provided as specified in the Archives Act 1983.

Focus on Selected Series

While all series in the archives are significant, there are a number of noteworthy records and items that speak to the breadth of the collection.

Colonial banking records

The colonial banking records are a rare source of information about the financial situation of those who settled in Australia during the 19th century. The earliest record is a legal document dated 1824 relating to the sale of 100 acres of land in the District of Petersham (now inner Sydney). The land, originally granted to John Austin by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1819, passed from Austin to Thomas Wylde on the 2 September 1824 for the sum of ‘ … one hundred pounds of lawful money of Great Britain …’.[8] In fact, it is one of seven documents held that relate to financial events concerning the same parcel of land during the years to 1837.[9]

The colonial banking records cover the era of convict arrivals. Contrary to the typical portrayal of convicts as penniless, many arrived with sums of money and were encouraged by the judiciary to place them in a bank including, specifically, Campbell's Bank and, from 1832, the Savings Bank of New South Wales. A significant early record held from this period is a ledger that lists the account balances of convicts arriving in the colony between 1826 and 1840, along with the name of the ship on which the convict arrived.[10]

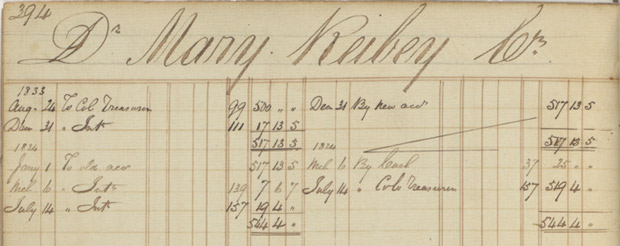

The colonial banking records from the Savings Bank of New South Wales also contain the bank accounts of those who would become prominent in Australian society. These include the convict turned successful businesswoman Mary Reibey, who is celebrated on the current $20 banknote, along with the accounts of the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt, the artist Conrad Martens and John Cadman (the convict who would establish a government shipping service). William Charles Wentworth (an explorer, author, barrister, landowner and statesman) and the prominent pastoralist and merchant John Blaxland, also feature as both were trustees of the Savings Bank. More generally, the colonial banking records enable examination of the establishment of households, estates and industry along with depositor behaviour in response to various types of economic events.

Figure 1 shows a ledger of the Savings Bank of New South Wales containing an entry for Mary Reibey.

Source: RBA Archives 5-1-1-1

Correspondence with the Governor

The archives contain correspondence with the Governors of the Bank since 1911. This correspondence captures significant exchanges between the head of the central bank and the Prime Ministers, Treasurers and officials of the day, along with correspondence with staff and members of the public.

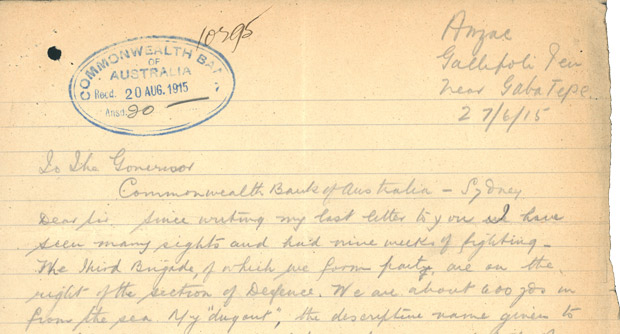

Among the most remarkable correspondence to survive are the letters sent to Governor Denison Miller (first Governor of the Commonwealth Bank) from staff serving in the First World War. Such was the relationship between the Governor and his staff that letters were sent to him from the battlefields. Staff detailed their experiences and would often conclude with good wishes for the future prosperity of the recently established institution. Figure 2 is a letter from Ernest Hilmer Smith to Governor Miller and was sent from the Gallipoli Peninsula, 27 June 1915. It gives an account of the Gallipoli landing.

Source: RBA Archives ST-PR-22

While letters from staff give insight to their lives and the character of the Bank, letters from citizens give insight to the central bank governor as a public figure. The themes of these letters vary with economic conditions and correspondence comes from those in all walks of life. Among the more notable correspondents is the cricketer Sir Donald Bradman, who wrote to Governor Bernie Fraser in April 1990 to encourage him in his efforts to maintain low and stable inflation.[11]

Glass plate negatives

The Bank has a collection of over 15,000 photographs and negatives that are of archival significance. This includes a subset of some 700 glass plate negatives that were created from 1913 when the Bank commissioned photographers to capture the construction of its Head Office and branches in towns and cities across Australia. While the focus of the photographs is on the Bank – and the anticipated role it would play as a national institution – the images capture the built environment of the early 20th century, street scenes, modes of transport, occupations, fashion and social life. The quality of images taken from a glass plate negative remains difficult to surpass, and this enabled the Bank to display them greatly enlarged on the façade of the Head Office building in Sydney in 2010 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Reserve Bank of Australia as the nation's central bank.[12]

Figure 3 is a glass plate negative that captures the view of the General Post Office in Martin Place (then Moore Street) in Sydney, from the roof of the Commonwealth Bank's Head Office building while under construction in 1915.

Source: RBA Archives PN-000679

London letters

The Bank has long had a London Office, and letters to and from London and Head Office commenced during the planning of the London Office in 1912. The records span the First and Second World Wars, the Depression of the 1930s, and other significant events of the 20th century, as a continuous series until 1975. Of particular significance are the reports written by Thomas Balogh, a prominent (and controversial) British economist, Oxford academic and advisor to British Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Balogh's fulsome reports on the state of the British and European economies were invaluable in keeping the Bank up to date on world economic and political events. They contained rich insight and data. The reports by Balogh are of particular value because detailed observations are made consistently in one voice from 1941 to 1964.[13]

Exchange controls

Australia's Exchange Control system was introduced in 1939 and ran until the floating of the Australian dollar in 1983.[14] It controlled all transactions between Australian and foreign entities, with only authorised banks, as agents of the Bank, permitted to convert foreign currencies into Australian dollars. Similarly, approval was also required for entities converting Australian dollars into foreign currencies, for travel or business. The Bank's archives contain details of these transactions, including samples of applications for foreign currency. Of particular interest are the files in the 1930s through to the 1970s relating to entertainers, actors and professional sports people who applied to have money earned in Australia transferred to their home countries. Celebrities who visited Australia and for whom the Bank has exchange control records include Bob Hope, Sammy Davis Jr, Laurence Olivier, Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole, Katharine Hepburn, Margot Fonteyn, Count Basie and Frank Sinatra, along with famous sporting teams and identities such as the Harlem Globetrotters.[15] The records also give insight to the development of professional sport, in particular World Series Cricket in the 1970s, with exchange controls applying to the establishment of the new cricket format and the now-famous cricketers who first played.[16]

Banknote design

The National Archives requires the Bank to hold samples of legal tender Australian banknotes, along with the information that is central to their creation. The banknote collection includes Australian banknotes of every denomination and series, beginning with the first series of notes in 1913 through to the present day. In addition, material associated with the banknotes, such as design elements, research and reference material, are held in the archives. More recently, the National Archives has determined that milestone printing plates are also to be retained.

In addition to the issued banknotes that form legal tender, the archives contain unissued banknotes and their design elements, along with early stages and designs of banknotes that were eventually released, but often with a very different look. Of special interest are the 1966 decimal currency banknotes that were designed by Gordon Andrews. As well as design work, the archives hold items used in designing the notes, including samples of the wheat and wool that feature on the $2 banknote. (See Figure 4.)

These banknote materials are stored securely in the Bank's archives and also in the Museum where they are on display to the general public. Digital exhibitions of them are also available on the Bank's Museum website, such as The Decimal Revolution which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the introduction of decimal currency in 2016.

Source: RBA Archives (Left to Right and Top to Bottom) NP-002025; NP-002027; NP-002830; MU-000375; MU-000364; NP-002016; NP-002831

Public Access

The Archives Act 1983 requires the Bank to make available to the general public those records that are in the ‘open access period’, defined in the Act as being 20 years after their creation. In addition to this, at the discretion of the Deputy Governor, the Bank chooses to make some information available 15 years after its creation, consistent with the Bank's goal of transparency.

The Bank's archivists act as intermediaries between those requesting access to the archives and the records. They locate information and records of relevance to the request, with this often entailing detailed research by the archivists. The Bank has a research room in which researchers and members of the general public can access the records under supervision from the Bank's archivists.

The Bank receives up to 250 requests for information from researchers each year. Reflective of the range of information, and the diversity of media and formats, research requests come from academics, postgraduate students, authors, journalists, numismatists, philatelists, genealogists and heritage architects. While a number of researchers visit the Bank in person, including from overseas, the majority of researchers are unable to do so. In this case, archives staff digitise key records that are then sent to them.

The Bank, like some other central banks, shares its records and their interpretation through official histories. Professor Boris Schedvin wrote the history of central banking in Australia for the period 1945–75, drawing on the Bank's archives.[17] The next instalment of the Bank's history, from 1975–2000, is being captured in a book by the Bank's historian, Associate Professor Selwyn Cornish of the Australian National University. His research is also facilitated by access to the Bank's archives.

To support greater access by the public and preservation of the records, the Bank commenced a project to digitise its archival collection. Given the scale of the archives, this is a major undertaking. However, nearly one-third of the records in the open access period have already been digitised. An ongoing program of digitisation will see all records in the open access period digitised within several years, with digitisation extending to other records subsequently. Records have been prioritised for digitisation according to their historic significance, preservation need and demonstrated demand.

At present, digitised records are sent to researchers either by email or via the Bank's external collaboration platform. Looking ahead, there are plans to build an externally facing digital archives that will enable the public to access these records directly and conduct independent research. A dedicated digital archives will also enable much more efficient search and identification of relationships between records. Public access to the Bank's research room will remain, with the physical properties of many records integral to their interpretation. Similarly, the assistance and research of the Bank's archivists will continue as a core feature of the public's access to this significant repository.

Footnotes

Jacqui Dwyer is the Head of the Bank's Information Department, which includes the Archives, and Virginia MacDonald is the Bank's Senior Archivist. The authors would like to thank the Bank's historian Selwyn Cornish for his knowledge sharing, and Information Department staff Bronwyn Nicholas, Anita Siu, Sarah Middleton-Jones, Elisabeth Grace and Carol Au for their assistance in preparing this article. [*]

This was because the Commonwealth Bank had become both a regulator of the banks and their competitor, and there were calls to remove any perceived advantage. [1]

Dr Coombs was appointed Director-General of the Department of Post-war Reconstruction in 1943 and was an author of the 1945 White Paper, Full Employment in Australia. [2]

An account of this can be viewed in a report by Kirkwood to the Bank's Administrative Committee in 1954 (RBA Archives SA-65-20, especially pages 27–30). [3]

The role was advertised in the Bank's Promotions Circular in October 1953, with Jack Kirkwood appointed to the role in January 1954 (RBA Archives COM-PC-2 – Circular Nos. 2453 and 254). [4]

An explanation of microphotography and its role in preserving records and making them accessible is documented in Kirkwood's report to the Bank's Administrative Committee in 1954 (RBA Archives SA-65-20, pages 23–27). [5]

The Archives Repository opened in 1957 in a custom designed space in the Bank's sub-basement. This brought the Bank's archival records together for the first time under a controlled system (RBA Archives SA-65-21). [6]

These periods are specified in the Bank's Records Disposal Authority, a legal instrument that specifies the length of time for which different types of Bank records should retained (and is published on the National Archives website). [7]

See RBA Archives 5-1M-6-5-1. [8]

The earliest document (1824) is a legal agreement between John Austin and Thomas Wylde. The latest document (1837) is a surrender of mortgage from the Savings Bank of NSW to Samuel Augustus Perry (RBA Archives 5-1M-6-5-1 to 5-1M-6-5-7). [9]

See RBA Archives 5-1-10-1. For further information regarding convicts and money, go to <https://museum.rba.gov.au/exhibitions/hidden-history-banking/>. [10]

A copy of this letter was published in the May 1990 edition of the Bank's staff magazine, Currency, along with Bernie Fraser's reply. [11]

For information on the 50th anniversary photographs that appeared on the Bank's facade, go to <https://museum.rba.gov.au/exhibitions/reflections-of-martin-place/>. [12]

The reports from Balogh are contained within the ‘From London’ series of letters (RBA Archives S-L). [13]

Don Sanders (then Deputy Governor of the Bank) discussed the history of exchange control in his paper ‘Control Over Foreign Exchange Transactions in Australia’ (1984) (RBA Archives GDS-S-25). [14]

These are contained within the Exchange Control Visiting Artists files, which date from 1939–1976. [15]

These records are held on file RBA Archives ECM-A-216. [16]

Schedvin CB (1992), In Reserve. Central Banking in Australia, 1945-75, Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards (NSW). [17]

References

Cornish S (2010), The Evolution of Central Banking in Australia, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney.

Morris J (2007), The Life and Times of Thomas Balogh: a Macaw among Mandarins, Eastbourne Sussex Academic Press.

National Archives of Australia, Our History, viewed 8 October 2019. Available at <https://www.naa.gov.au/about-us/our-organisation/our-history>

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives 5-1M-6-5-1 (Savings Bank of New South Wales - Sydney (Head Office) - Mortgage (Investment) Department - Legal Documents - Land Release, John Austin to Thomas Wylde), 2 September 1824.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.C.41.1 (Banking Department - Exchange

Control - Monetary Control Policy - Visiting Artists), 1939 – 1953.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.C.41.2 (Banking Department - Exchange Control - Monetary Control Policy - Visiting Artists), 1954-1955.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.C.41.3 (Banking Department - Exchange Control - Monetary Control Policy - Visiting Artists), 1956 – 1957.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.H.98 (Banking Department - Exchange Control - Monetary Control Policy - Visiting Artists), 1958 – 1959.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.L.189 (Banking Department - Exchange Control - Monetary and Securities Control Policy - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1961 – 1965.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.M.193 (Exchange Control Department - Monetary and Securities Control Policy - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1966 – 1967.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.N.214 (Exchange Control Department - Monetary Control Policy - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1968 – 1969.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.P.258 (Exchange Control Department - Monetary Control Policy - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1971.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.Q.305 (Exchange Control Department - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1972.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.R.329 (Exchange Control Department - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1973.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.S.321 (Exchange Control Department - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1974.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives B.1.1.1.U.312 (Exchange Control Department - Policy Files - Visiting Artists), 1976.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives ECM-A-216, (Exchange Control - Monetary Control - Applicants - World Series Cricket Pty Ltd & Schedule – Intermediate), 1977.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-19 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Liaison with Commonwealth National Library, Archives Division: Visit of Dr T.R. Schellenberg to Bank), 1954.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-20 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Report to Administrative Committee), 1954.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-21 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Archives Repository - Transfer of Sub-Basement Records to), 1956–1960.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-23 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Quarterly Reports to Secretary), 1954–1963.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-24 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Quarterly Reports to Secretary), 1963–1965.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-25 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Programme - Archives & Records Management Section 1 – General), 1963–1964.

Reserve Bank of Australia Archives SA-65-27 (Secretary's Department - Archives - Establishment of Bank's Archives - Programme - Protection of Vital Records), 1964–1965.

Reserve Bank of Australia, Origins of the Reserve Bank of Australia. Available at < https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/origins-of-the-reserve-bank-of-australia.html>

Reserve Bank of Australia (2010), Hidden History of Banking. Available at <https://museum.rba.gov.au/exhibitions/hidden-history-banking/>

Reserve Bank of Australia (2010), Reflections of Martin Place. Available at <https://museum.rba.gov.au/exhibitions/reflections-of-martin-place/>

Steven M (1966), Campbell, Robert (1769-1846), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol 1, Melbourne University Press, viewed 17 October 2019. Available at <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/campbell-robert-1876>